Born in the 1930’s in a small village in Japan, Oe grew up under the tutelage of both his grandmother and mother, women, who believed in the power of art and the written word. In A Quiet Life the protagonist is female and feels close affinity to her mother, a far more approachable and nurturing parent. Oe’s childhood, his close relationships with females, and his connection with both rural and urban Japan provides his work with a scope that few novelists achieve.

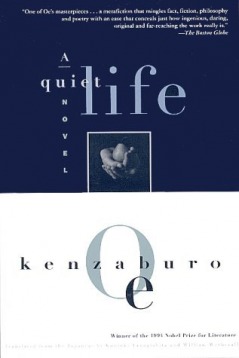

Over the course of forty-eight hours, I devoured A Quiet Life. This haunting novel is narrated by Ma-Chan, the twenty-year-old daughter of a famous novelist. Born into a family of both talent and madness, Ma-Chan falls into the role of dutiful daughter, helping her brilliant and flawed kin to navigate through the world. Her father leaves for America in order to overcome what the family terms, “a pinch”. Her father’s depression requires the support and presence of Ma-Chan’s mother, and Ma-Chan is left in Japan to care for the other genius in the family, her talented yet mentally handicapped brother.

Becoming the head of the household, Ma-Chan narrates her family’s experience without the presence of her parents. Eeyore, her mentally handicapped brother, requires her utmost attention and support. His passion and talent for music composition elevates an otherwise pitiable character. Ma-Chan must move with her brother, step-by-step, and while clearly an exhausting task, Ma-Chan has no bitterness. Her other brother, an independent and largely ignored teenager, drifts in and out of the novel. Both siblings, in their normalcy, do not demand the attention or praise that their father and other brother bring forth.

And this is what I enjoyed most about the novel: the careful distribution of care amongst groups of people, amongst families. There seems to be this unwritten code that determines what each member needs in order to survive, in order to thrive, and in A Quiet Life the reader is privy to an otherwise private contract. As is common in most cultures and societies, the burden of care falls on the women. Both Ma-Chan and her mother are the responsible parties keeping the male savants functioning, and one wonders what would have happened if the needs had been reversed, if it was the women with the emotional or mental imbalances.

This novel is the simple telling of a triad of adult siblings surviving without the presence of their parents. Ma-Chan records their days in a diary fashion, focusing on what she deems most important, the conversations, the intellectual stimulations, the progress of Eeyore, and her fears for his well-being. As the novel unfolded, I connected with Ma-Chan. I understood the steady and aching toll of caring for one who cannot fully care for himself. But Oe does not let the reader leave with the belief that this sibling relationship was one-sided; Eeyore may be dependent on Ma-Chan for most everything, but as in all human relationships, even the weakest member can provide necessary, even vital support. Read this novel, if you can find it, or perhaps pursue another work by Oe and let me know your impressions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed