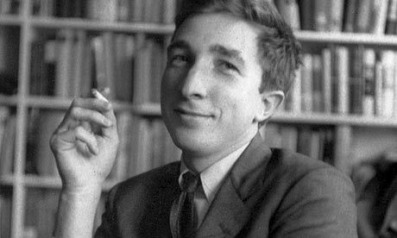

John Updike wrote, on average, a novel every year; one full, breathing novel being birthed every 12 months. As I struggle through the beginning pages of my own manuscript, I have to shake my head when I consider Updike's enviable output. Even more astounding, his work and prose were uniquely his own; the novels he produced were not shoddy pieces of writing, but instead were distinctive and unparalleled additions to the literary canon.

Many of Updike's novels are populated with average American individuals who face the personal and every-day crises and passions that human beings suffer. Crises of religion, of relationship, of satisfaction with family or job, and of course, the passion and possession of sexuality. These are the themes that interested Updike, and are they not some of the same themes that still interest the collective conscious of our country?

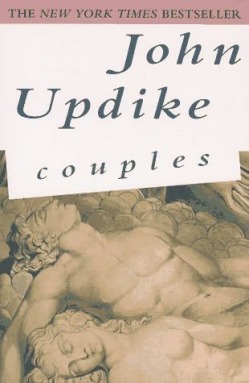

But what makes Updike's exploration of these common people and themes extraordinary is his often blinding and exhilarating prose. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Updike's prose is a mixture of arcane and often crass vocabulary. He uses words that people have either forgotten exist or are too embarrassed to say in public. In Couples, Updike delves into female and male anatomy with no reserve. His sentences can be graphic, he uses precise language to describe those oft unspoken acts, but then he will unleash his literary prowess and cloak sexual situations in wordy and often beautiful metaphor. The reader must allow herself to float back and forth from these distinct expressions in order to appreciate the flow of his work.

Updike's prose is rich. He is not an author to be quickly scanned. His attention to the mundane world of everyday living is astounding, and it makes the reader aware of the quiet beauties and the tragedies in his or her own life. By dissecting and then eloquently describing the every-day, Updike conveys the importance of living. When a small dinner party with friends is described in such thrilling and complicated language, the reader can't help but place more importance on an otherwise mundane event. The fact that Updike cares enough to describe these every-day occurrences shows the reader that the common-place is of grave importance.

In Couples, Updike disects and displays the complications and the tragedies that can arise in a group of middle-aged Americans, all living in a small and relatively affluent town. In typical Updike style, these couples end up in an array of sexual situations, and the term "swinger" is particularly apt. The main protagonist is just as self-centered as one might presume an Updike character to be, but as the novel plugs along, the reader finds herself allowing some of his behavior to slip, finds herself mirroring Updike's forgiving portrayal of an otherwise depraved individual. At some points in the novel, I stopped myself in order to regain my moral perspective. "This really is unacceptable," I would tell myself, and then continue to traipse through Updike's New England town.

The number of couples in this novel is overwhelming, and the various pairings easily become confused. Is she sleeping with him? When did they hook up? Did they both sleep with her? Does she know about what happened last summer? These questions abound and despite spending several days pouring over this book, they don't abate. Even as I flip though the pages today, I find myself asking the same questions. There are far too many "couplings" in Updike's novel for a casual reader to track. But the proliferation of illicit interaction certainly plays a role in Updike's purpose; Updike's inclusion of these pairings displays the pervasiveness of these questionable sexual encounters. There is one key relationship that the novel focuses on, a relationship in which the full outplay of betrayal and passion can be seen, but he includes these others in order to immerse the reader in this sexually loose world; without them, the main relationship seems more foreign, more reprehensible, and the reader can offer the couple less grace.

If someone was to ask if would recommend this novel, I would hesitate, but then encourage an avid reader to take Updike and this novel with a questioning yet appreciative mindset. Undeniably, there are aspects of Updike's portrayals that bother me, that bore me, but his prose is uniquely his own, rich with description and populated with unique vocabulary. He is worth a read, and this novel happens to be my favorite of his that I've read thus far.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed