The protagonists in many of Brookner's novels are women who have been ignored or misunderstood. They live relatively narrow lives. Although well-educated and financially stable, these woman are often unattractive, or at least past their sexual prime, and struggle to find their place in the world.

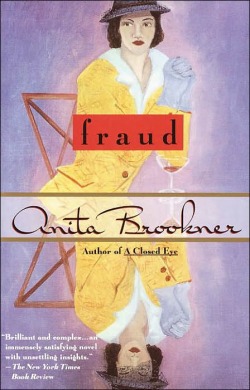

Anna in Fraud fits this typecast well. When the book opens, the reader is introduced to Anna through the tinge of a police investigation. Upon her missing several appointments, the law has been summoned to determine where Anna might have gone. In the minds of her acquaintances, there can be no possible explanation for Anna's disappearance other than a kidnapping or violent crime.

After all Anna is in her fifties, unmarried, and lives a simple, selfless life in a small flat in London. To the outside world, she sacrificed her future to care for her invalid mother, a beautiful and selfish woman who entangled herself in an unhealthy affair. With the death of her mother, Anna found herself old and alone, with little prospect for intellectual or emotional growth. At least, this is what the outside world sees.

But the wonder of Anita Brookner is her ability to move a plot forward through the inner workings of her characters. Dialogue or events do not move the reader forward in her novels, but instead a rich inner life is dissected and presented for our perusal. Although it may appear on the surface that Anna lives a dull life, Brookner breathes vitality into her protagonist by revealing to us her thoughts and past actions.

As a contrast to the selfless and demure Anna, Brookner alternates perspectives to a more vivacious woman, Miss Marsh. Miss Marsh serves as an apt foil to Anna, both needing her sympathy as an older woman and despising Anna's decisions to serve her mother and to live a quiet life. Much judgment and harshness flows from her mouth, but as the novel unfolds we learn how incorrect her initial assumptions were.

While the world might perceive Anna as a staid virgin, the surface doesn't begin to reveal the depths inside each human soul. Anna turns out to be a far more complex and daring woman than her social circle imagined. While her mother's illness kept her close for year after year, it is made clear that, "She had escaped from a prison cell and she was determined to never again be imprisoned" (129).

The eloquence of Brookner's prose is enough to compel my strong recommendation, but the unique composition of the book, told through the perspective of many different characters with varying intents, seals my approval.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed